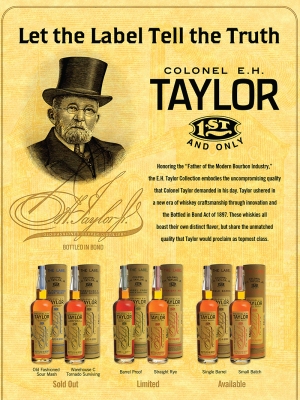

Here is my threatened follow-up post on some of the issues that came up when I was idly looking up the history of Colonel E.H. Taylor for my review of his namesake Small Batch bourbon released by Buffalo Trace. Before I get into it, let me first say what this is not and what it is.

It is not scholarship or even journalism: if I were doing either of those things I would spend months or weeks researching the subject. I would read every book on bourbon history to see to what extent and how this material has already been written about; I would investigate the archives of the distilleries and of the relevant locations (Frankfort, KY, for example); I would read historical studies of the Civil War and Reconstruction; I would interview experts like Chuck Cowdery, Mike Veach and Reid Mitenbuler. I have done none of these things because this is not scholarship or even journalism (and should not be confused with or held to the standards of those enterprises).

What this is is a blog post: it’s exploratory, it’s speculative, it’s a clearing of space in my own head which might possibly lead to more detailed exploration down the road or it might not; hopefully it will invite responses from people who can fill in all the things I would know if I’d done the research and point me to other places to look; and, even if it’s all redundant, hopefully it will spur some discussion: there are subjects which even if already known benefit from regular discussion and I think this might be one of them.

Okay, a quick recap for those who didn’t read my initial post on the subject and don’t want to click over now to do so: I noted that I found it interesting that the few accounts of E.H. Taylor Jr.’s life that I could find online, including on Buffalo Trace’s website, seemed to omit his life and activities before the end of the Civil War. This I found striking both because he was born quite a bit earlier, in 1832—i.e he was already in the prime of his life in the 1860s—and because he was apparently a purchasing agent for the Union during the war, and therefore on the right side of history.

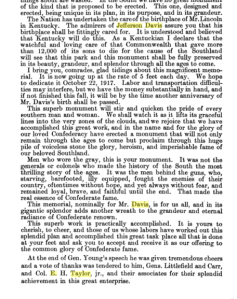

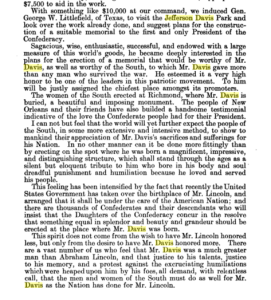

That post was actually written a couple of months ago, and only posted on Wednesday. After it was published I idly did a Google search for “E.H. Taylor Jefferson Davis” and came up with something unexpected. (I should say first that I did that search because in the post I’d noted that Taylor was apparently related to Jefferson Davis—where I’d originally got that I don’t remember anymore: if you can corroborate or correct please do so below.) What I found was an account of a speech given in 1917 by a General Bennett H. Young about the Jefferson Davis memorial monument, which was then just under construction. The interesting part was the singling out of Col. E.H. Taylor as one of the major donors and the very ripe language used to glorify Jefferson Davis and the Confederate cause. Screenshots of the text of that speech are in the comments of Wednesday’s post, but I’ll repost them here (click on the images alongside to expand them).

That post was actually written a couple of months ago, and only posted on Wednesday. After it was published I idly did a Google search for “E.H. Taylor Jefferson Davis” and came up with something unexpected. (I should say first that I did that search because in the post I’d noted that Taylor was apparently related to Jefferson Davis—where I’d originally got that I don’t remember anymore: if you can corroborate or correct please do so below.) What I found was an account of a speech given in 1917 by a General Bennett H. Young about the Jefferson Davis memorial monument, which was then just under construction. The interesting part was the singling out of Col. E.H. Taylor as one of the major donors and the very ripe language used to glorify Jefferson Davis and the Confederate cause. Screenshots of the text of that speech are in the comments of Wednesday’s post, but I’ll repost them here (click on the images alongside to expand them).

This made me think that it was less surprising that Buffalo Trace didn’t mention Taylor’s activities on the Union side during the Civil War—after all, if you play that up then it’s quite an omission to leave out his activities and sympathies later in life. Plus, as a number of people pointed out to me, it’s not unlikely that some fraction of the bourbon market might in fact not look with favour on his having been on the Union side during the war—see, for example, this post by Chuck Cowdery which mentions that until 1984 the Rebel Yell brand was only available south of the Mason-Dixon line. In fact, it’s not clear what Taylor’s actual sympathies were during that period either: see this summary of the Taylor-Hay family papers held by the Filson Historical Society: you’ll see that the clients of his bank before the war included a number of slaveholders.

In private conversation (which I have permission to paraphrase), Sku pointed out that none of this is particularly surprising: he hazarded that if we looked closely into the activities of your Jack Daniels, your Elijah Craigs, your Evan Williams, your George Dickels etc. we’d likely come up with very similar stuff. As Sku noted, these were all privileged white southerners living in antebellum and recent post-Civil War South—indeed you don’t have to look very hard to learn that Elijah Craig was a slaveholder (though you won’t find that on this Heaven Hill brand ambassador’s page who otherwise replicates language from the Wikipedia page that mentions it!). In another brief private conversation (which I also have permission to paraphrase), Reid Mitenbuler said much the same. He pointed out to me that Jim Beam’s middle name, Beauregard, was for a Confederate general and that the Samuels (of Maker’s Mark) supported the Confederacy. And I’m sure many of you who’ve read up on the distilleries can add to this tally. Even if knowledge of the specific E.H. Taylor-Jefferson Davis stuff isn’t widely known, it’s certainly not shedding light on a more general aspect of bourbon history that is in any way unknown. (To be clear neither Sku nor Reid M. are in any way excusing any of these men for being men of their times.)

In private conversation (which I have permission to paraphrase), Sku pointed out that none of this is particularly surprising: he hazarded that if we looked closely into the activities of your Jack Daniels, your Elijah Craigs, your Evan Williams, your George Dickels etc. we’d likely come up with very similar stuff. As Sku noted, these were all privileged white southerners living in antebellum and recent post-Civil War South—indeed you don’t have to look very hard to learn that Elijah Craig was a slaveholder (though you won’t find that on this Heaven Hill brand ambassador’s page who otherwise replicates language from the Wikipedia page that mentions it!). In another brief private conversation (which I also have permission to paraphrase), Reid Mitenbuler said much the same. He pointed out to me that Jim Beam’s middle name, Beauregard, was for a Confederate general and that the Samuels (of Maker’s Mark) supported the Confederacy. And I’m sure many of you who’ve read up on the distilleries can add to this tally. Even if knowledge of the specific E.H. Taylor-Jefferson Davis stuff isn’t widely known, it’s certainly not shedding light on a more general aspect of bourbon history that is in any way unknown. (To be clear neither Sku nor Reid M. are in any way excusing any of these men for being men of their times.)

So, why am I going on about it then? Well, I’m fascinated by this odd dance that so many established American distilleries do with what is, to say the least, a very complicated history and I’m interested to hear what regular bourbon drinkers make of it. Almost all these distilleries have hung their hat on “Tradition” and “Heritage” (as Patrick pointed out in the comments on Wednesday’s post). This is not in and of itself anything unusual. The United States is a country where claims of established tradition/history are always going to be prized—probably because actual national history doesn’t go back very far. This is why “artisanal” hipster producers in Brooklyn who have nothing in common with Southern distillers also seek to project an invented old-timey tradition through playing dress-up. The established bourbon distillers, on the other hand, actually have a real tradition, a real history going back 150 years or more at this point and so it’s no surprise they want to make sure we know it. But in its telling they don’t distinguish this history from the stories they continue to tell of the men whose names they put on bottles.

T.W. Samuels of Maker’s Mark. The distillery’s website presents a very abbreviated history of the man.

To put it another way, a Tradition of Distilling is not the same thing as a Tradition of Founding Distillers. The former can, with care, be presented somewhat neutrally: “We’re special because we’re doing something that we’ve been doing for a long time, our practices are traditionally tested and established and this is why our whisky is so good”. This is, by and large what we see in the world of Scotch. Almost all those distilleries were also established in the 19th century. And I have no doubt that if we looked closely we’d find raving imperialists under many a pagoda roof. But the Scotch industry, by and large, emphasizes its tradition not through citation of these figures but through the distilleries themselves and the story of traditional craftsmanship. Brand names of the “Founder’s Reserve” variety abound but very few whiskies are named for actual figures.

The problem with the Tradition of Founding Distillers is that it doesn’t really have to be read against the grain to reveal men who, in addition to founding distilleries, held racist ideologies and supported abhorrent causes. Now the original sins of slavery and the genocide of native Americans are of course central to most American stories—in no way do I mean to single out bourbon here. But it’s hard for me to come up with too many iconic American industries that slap the names and faces of racist founders on their products and websites and in a sense force you to commemorate them with each purchase: “We’re special because we were established by this guy and we make whisky the way he did or liked [but let’s not talk too loudly about everything else he liked and did at the same time]”.

I’m not suggesting that bourbon distilleries should abandon their past (or simply fudge it by not mentioning it at all). But to repudiate (some aspects of) the past is not to deny it. You can not only acknowledge the roots of your distillery and industry in a deeply racist milieu, you can address this on your distillery tours and on your websites. You can be a greater, more visible supporter of the causes of racial justice that remain woefully necessary. You can certainly acknowledge you were founded by someone who held racist views and/or was an apologist for the Confederacy well into his days without naming a premium line of bourbons for him. Personally, learning about E.H. Taylor’s past makes me reluctant to put a bottle named for him on my bar (though it doesn’t make me reluctant to buy Buffalo Trace products per se).

Now I’m going to await the arrival of a bunch of books that I look forward to reading carefully. It may well be the case that everything I have said here has been said before and better by them. In which case this has been a wonderful use of your and my time. You’re welcome!

Here are the books I have ordered (please note that these Amazon links are through my Associates account and so if you purchase them, or anything else, by following these links I will receive a small commission):

- Gerald Carson, The Social History of Bourbon.

- Charles Cowdery, Bourbon Straight.

- Henry G. Crowgey, Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking

- Reid Mitenbuler, Bourbon Empire.

- Michael Veach, Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage.

If there are others you’d recommend I read that might cover the issues above, or if there are articles or other blog posts on the same subject you’d recommend, please write in below.

MAO,

Meme heavy back and forth about the recent “controversy” regarding the superbowl halftime 50 halftime show has forced me to examine the feelings of others (a generally abhorrent practice). I have concluded the following about symbology:

1.) Powerful symbols mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people. Often, at least one group of people is going to be offended by said symbol. I’ve decided that the current intent of the symbol bearer should factor heavily into whether said symbol should be interpreted as offensive.

2.) Marketers and “artists” tend to take advantage of powerful symbols by throwing them out there with some vague hints as to meaning and watching the ensuing chaos. Maybe the symbol will be interpreted as racist, maybe as a hearkening back to simpler times, maybe one can interpret a dozen other meanings. What I interpret the symbology of these historical figures to mean is that their names and fake shitty stories sell or at least poll well. Why that is, I am not certain. Why these brands sell well is as interesting to me as the true history of the people used in their marketing. Buffalo Trace decided to premiumize a line of mostly bottled in bond whiskey, and happened to own the Taylor trademark. Savvy branding has allowed them to sell this line at a 100-300% premium to most other bottled in bond brands.

3.) Powerful/famous people are very often not particularly good people. Given Taylor’s infamous litigiousness, I think it is safe to assume he fits that pattern.

4.) Racism was rarely a concern for Marketers until relatively recent times. My parents certainly remember growing up in the midst of segregation and Jim Crow laws.

5.) Many, if not most of these named products fall into the premium or super premium market segments for American Whiskey.

6.) Given the lack of variety in location or catchy Gaelic translations available to disguise catchy names like “hill by that lake over yonder” distillery, I am not surprised Marketers love using mostly made up historical figures instead.

7.) Numbered lists are awesome.

Ultimately, I almost think it appropriate revenge for these almost certainly not nice people to be turned into historical parodies of themselves. E.H. Taylor isn’t a revered historical figure. He is a sock puppet used to sell bourbon. At least it is mostly 50%+ abv, bottled in bond bourbon.

I certainly do appreciate the thought provoking topic.

Eric

LikeLike

MAO,

An interesting parallel to this topic is the portrayal of Scottish people and culture (mostly Gaelic, I guess) by the Scotch Whisky industry. Ralfy takes a fairly dim view of it, and discusses it on occasion in his video reviews. A semi recent example I can think of is his Bunnahabhain Toiteach review.

Eric

LikeLike

Everyone draws their own lines. I’ve bought a bottle of Catoctin Creek’s Mosby’s Spirit, named for Confederate war hero John Mosby, and never thought that had any pro-Confederacy, much less pro-slavery, implications. On the other hand, there are beverages I would never buy because I find the names inappropriately coarse or juvenile (craft beers seem particularly susceptible), while I’m sure other people buy them *because* of the coarseness. And there are companies whose products I don’t buy because I don’t like the company, without having any problem with the products themselves.

In the case of Kentucky bourbon, the names don’t mean anything to me personally, so I’m inclined to judge them based on what they mean to the companies that sell them. E. H. Taylor may have been an awful man, he may have been a saint, but he’s on the bottle as founder of a distillery, so it’s a don’t-care for me. I wouldn’t buy a Simon Legree Bourbon, so I suppose my personal line is somewhere between the two.

As for distilleries teaching visitors what rotters their founders were, I suppose they could, but I’m not sure distilleries are the best sources of information on the evils of racism, and frankly I don’t go to distilleries to be educated as a good citizen of today. A donation to a real history museum might be a better way to address, if not entirely redress, the sins of the founders. (Should today’s generation of distillery founders post their answers to political and social surveys in their tasting rooms, so we can know if they are men and women of their time?)

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughtful comments, Eric and Tom. Lots to think about and respond to, so I’ll do it bit by bit. And maybe others will chime in too in between.

I’ll start with the second part of Eric’s second point: that at Buffalo Trace, at least, the use of these historical figures’ names (Taylor, Stagg, Weller) is on their super/premium lines. Beam does the same with Basil Hayden. I’ll point out though that other distilleries put such names up and down their ranges: Elijah Craig, Evan Williams, George Dickel, Jack Daniel’s, regular Jim Beam etc. As to why proper names should be so disproportionately used in selling American whiskey as opposed to pretty much every other category of liquor, I’m not sure, but it does appear to be so. Is it a case of merely following established practice when putting out (new) brands? Or is it, as I suggested, considered the easiest way to evoke old-timey “tradition”?

That said, other iconic distilleries/brands don’t go down this route: Maker’s Mark, Four Roses, Wild Turkey, for example—even though all these distilleries’ origins are also in the mid-1860s. Of course, it might simply be the case that these distilleries don’t have names associated with their founding/history that trip off the tongue in quite as harmonious or evocative a manner as Elijah Craig or E.H. Taylor. But it certainly shows that tradition and iconicity do not require the use of founders’ names.

It does seem to me that when you bring the names of historical figures across for your marketing purposes it’s hard not to bring their history with them. Even if your intention is not (as I very much hope) to commemorate everything about these people, if you’re presenting a sanitized version of them in the process of evoking “heritage” then, well, I think you’re in sticky territory.

On that note, as I head to lunch, let me quickly flesh out a parenthetical aside from the post. I noted that one of Heaven Hill’s brand ambassadors leaves out some messy history in his account of Elijah Craig while replicating language from a Wikipedia article that includes that messy history. Here’s what I’m referring to:

1. Here’s the Whisky Professor, Bernie Lubbers on Elijah Craig: “Craig continued to prosper, coming to own more than 4,000 acres (16 km2) and operating a retail store in Frankfort, KY. ”

2. Here’s Wikipedia on Elijah Craig, emphasis added: “Craig continued to prosper, eventually owning more than 4,000 acres (16 km2) and enough slaves to cultivate it, and operating a retail store in Frankfort.”

I’d submit that his being a preacher and laying out the plans for a town (both of which Lubbers mentions) are no more relevant to his status in bourbon history than his being a slave owner. Of course, he was not the only white slaveowner of his time but he was also not the only preacher or town planner of his time. It certainly complicates the ending of Lubbers’ expurgated history: “The Kentucky Encyclopedia refers to the Kentucky Gazette for his eulogy, ‘He possessed a mind extremely active and, as his whole property was expended in attempts to carry his plans to execution, he consequently died poor. If virtue consists in being useful to our fellow citizens, perhaps there were few more virtuous men than Mr. Craig.'”

LikeLike

The bit of history I have read suggests that Taylor was first and foremost a businessman. He would at one point become nearly bankrupt, eventually left what is now Buffalo Trace and then started a distillery that is now the Old Taylor “Castle” distillery that was recently purchased and is being refurbished. For all I know Taylor could have been playing both side during the Civil War and/or because of his association with the Union he may have gone out of his way to play up his Southern “roots” after the war to get back into good graces with the locals after the war.

LikeLike

That seems not unlikely. Though I have to say that considering he was the mayor of Frankfort for 16 years he may not have needed to be one of the biggest contributors to the Jefferson Davis memorial at the end of his days to prove his credentials. But I don’t want to make this about E.H. Taylor or Buffalo Trace (the Jefferson Davis memorial is of course a national monument now)—it’s just what got me thinking about the issue.

LikeLike

Dear AO

E.H. Taylor was a descendent of President Zachary Taylor. Jefferson Davis’ first wife was Sarah Knox Taylor, Zachary Taylor’s daughter.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

(By the way, Bernie Lubbers is also the star of this post by Sku.)

LikeLike

MAO,

Some good points on your part. Advertisers are forever attempting to get the good without any of the bad.

One thing I will add is that Four Roses itself may not even be completely certain why they are called Four Roses, though they tell the most romantic version of the history of their name if you take the tour. I don’t recall where–maybe Straight Bourbon–but I did read a pretty fascinating history of the brand at one point. I wish I had the link to share. Of course, I don’t really worry too much about their name, because I’m a card carrying Four Roses cultist.

My point is that even Four Roses, vaunted bastion of bourbon quality and integrity (bourbon qualtegrity, to Buckminster Fuller it up) is happy to feed you a line about the origin of the distillery’s name.

As to Bernie Lubbers, I am in the minority in that I think EC12 is over oaked and would benefit from being an average of 8-9 years of age. Lubbers is still a smug sack of crap, though.

LikeLike

From what I’ve heard, the Four Roses’ history is sort of the product of the marketing department (Paul Jones, Jr did exist for one thing but the rest of the story is probably baloney). It’s why Jim Rutledge apparently doesn’t like talking history (why should he?) at events and prefers to focus on the bourbon instead.

LikeLike

Clay Risen writes in the New York Times about Jack Daniel’s recent decision to come to terms with and embrace a crucial part of its history.

LikeLike

Above all else distillers were capitalist, capitalists that needed to sell their products.

I would harken you back to a scene in a movie, I know a movie, but there is often truth in movies. In the movie The Outlaw Jose Wales there is a scene with the ferry boat operator and the “medical elixir” salesman where in the ferry boat opeat or say something similar to this: “I’ve learned in my line of business you have to learn to sing the Battle Hymn of the Republic, and Dixie at the same time.”

What well respected distiller wouldn’t do the same thing to ensure sales of their product?

LikeLike

“with equal enthusiasm”, not ” at the same time”

LikeLike

I’m sure Buffalo Trace’s new E.H. Taylor tour will go into these matters.

LikeLike

Please read this great piece by Clay Risen about the gap between Jack Daniel’s claims that it would incorporate the legacy of Nearest Green into its distillery history and tours and the actual reality until Fawn Weaver, an author, stepped in.

LikeLike

First of all I am not in the least racially sensitive. Neither am I yankee sensitive. And I like the idea of drinking bourbon named after Confederates and Confederate sympathizers. Furthermore I am not interested in sissified politically correct products. Finally though thanks for the article. Now down the hatch with some rebel yell.

LikeLike

Quit trying to water down history. You can complain all you want about history but it is exactly what it is. Don’t erase the past, because it hurts your feelings, embrace it even if you don’t understand or resonate with it. The industry doesn’t need to change, you do!

Tolerance isn’t for everyone, especially when you complain about their history. Confederate or Union, we are all American…start acting proud for once and enjoy that bourbon!!

LikeLike

Did you finish your research on this?

LikeLike

Do you celebrate holidays? Do research on the origins of each of the major holidays and tell why you ok with celebrating them but drinking bourbon named after some dead racist is not cool. Or how about researching the full version of the national anthem- which is profoundly racist. Nazi regime and Audi, BMW and Porsche….You know what, there’s a Very Good chance that one of your forefathers was a racist. Does that mean that you are a racist and you should be ashamed of your lineage? No. Think before you write (your content is well written- just incredibly short sighted) Bourbon is a alcohol beverage that is revered by many. Leave it at that and quit trying to stir up contentious among people by claiming bourbon is something it’s not.

LikeLike

E. H. Taylor VI, please fuck off.

-Patrick

LikeLike

It might be more to the point to say that bourbon makers should stop making their bourbon into something it’s not, including “revered” (?!) in terms of tales of proud, but heavily edited, “heritages”. In whisk(e)y, heritage and tradition have a lucrative appeal in general – everyone wants to believe that distilling elves are handcrafting every bottle just for them, exactly as it was never done centuries ago in Scotland, Ireland and elsewhere. In bourbon, that kind of rational disconnection is compounded by a certain mythical accommodation that many Americans have made with the Antebellum period and the Civil War itself: a romantic notion of a special civilization and a Lost Cause now gone with the wind but that should be remembered, and even celebrated, by sanitizing American history… and personal history. Along with those on the Revolution and the Old West, many people’s ideas on the Civil War continue to be one of the central national myths.

LikeLike